The Persecution Of German Jews

In 1933 Adolf Hitler became Germany’s Chancellor. He had gained power thanks to a heady brew of violence, funnelled discontent, grand promises, theatre and chicanery. Once in government he used the power of the state to undermine democratic institutions and to lay the foundations of an authoritarian dictatorship. An important element of his power-winning strategy was to focus Germans’ angry post-war frustrations on attacking scapegoats, on attacking minorities like the Communists and the Jews. Hitler didn’t invent Anti-Semitism, but he was to give it a unique virility, energy and purpose. Ultimately, he dedicated the power and reach of the Nazi State to the pursuit of his fantasy of a Jew-free world. It was to prove a deadly ambition and the Jews an easy target.

At first Hitler contented himself with using the SA, the Storm Troopers or Brown Shirts, to mount a noisy and nasty campaign against them. The Nazi newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter, ran endless articles attacking Jews and individual attacks on Jews and their businesses grew. Later, after 1933, this situation worsened until, by 1935, German Jews faced legal persecution enshrined in the Nuremburg Laws. These, for example, deprived Jews of their German citizenship and increasingly isolated them from normal life by forbidding any social intercourse between Jews and non-Jews or Aryans. As a consequence, life for most Jews steadily worsened after 1935. On November 7th, 1938, a young Jew, furious at the treatment meted out to his family in Germany, shot dead a diplomat at the German embassy in Paris. By the 10th Joseph Goebbels had unleashed an organised attack on German Jews as a punishment.

The night’s toll made grim reading: ninety-one Jews killed; four hundred synagogues burnt down; 7,500 Jewish-owned businesses attacked and over 30,000 Jewish men sent to concentration camps. Kristallnacht, “The night of the broken glass”, marked a serious turning point in the Nazis’ treatment of the Jews and a significant increase in the number of Jews planning to leave their homes was soon evident.

Rescuing The Jews: Kindertransport

Despite huge difficulties, strenuous efforts were made, both inside and outside those countries which Hitler came to control, to get as many Jews as possible to places of safety. The Quakers, British Jews and others who had watched developments in Germany with growing concern, accelerated their efforts. Evacuation was usually by train to a channel port and then boat to England and the first train left Germany on December 1st, 1938, soon after Kristallnacht. ‘Kindertransport’, as this concentration of effort became known, set about arranging for groups of Jewish children to be brought to the UK as a staging post en route to other countries or for a period no longer than two years.

The British Government, worried even then by a combination of Victorian angst over overpopulation and by its concomitant immigration, had insisted that only Jewish children would be allowed temporary residence and even they would have to be sponsored by UK citizens to the hefty tune (in the currency values of the time) of fifty pounds. Contrary to present day claims, the British Government did not welcome Jewish refugees with open arms. Kindertransport successfully evacuated some 10,000 Jewish children before the war began and often did so in difficult and fraught conditions. The evacuation only stopped when the war began in September 1939.

A number of Jewish children, rescued in this manner, were to come to East Lothian. Their principle home was as pupils in Whittingehame Farm School. It is difficult to imagine how hard it must have been for young children, most of whom, of course, spoke no English, to separate from their parents and place themselves in the hands of strangers to move to often unknown destinations. One person who can remember, rather than having to imagine, is Stefan Brienitzer. Better known as Stevie Brent, Stefan was born in Breslau, a former German city which is now part of Poland. Stefan escaped via Kindertransport in July 1939.

Stefan Paul Ludwig Brienitzer: Kindertransport Evacuee

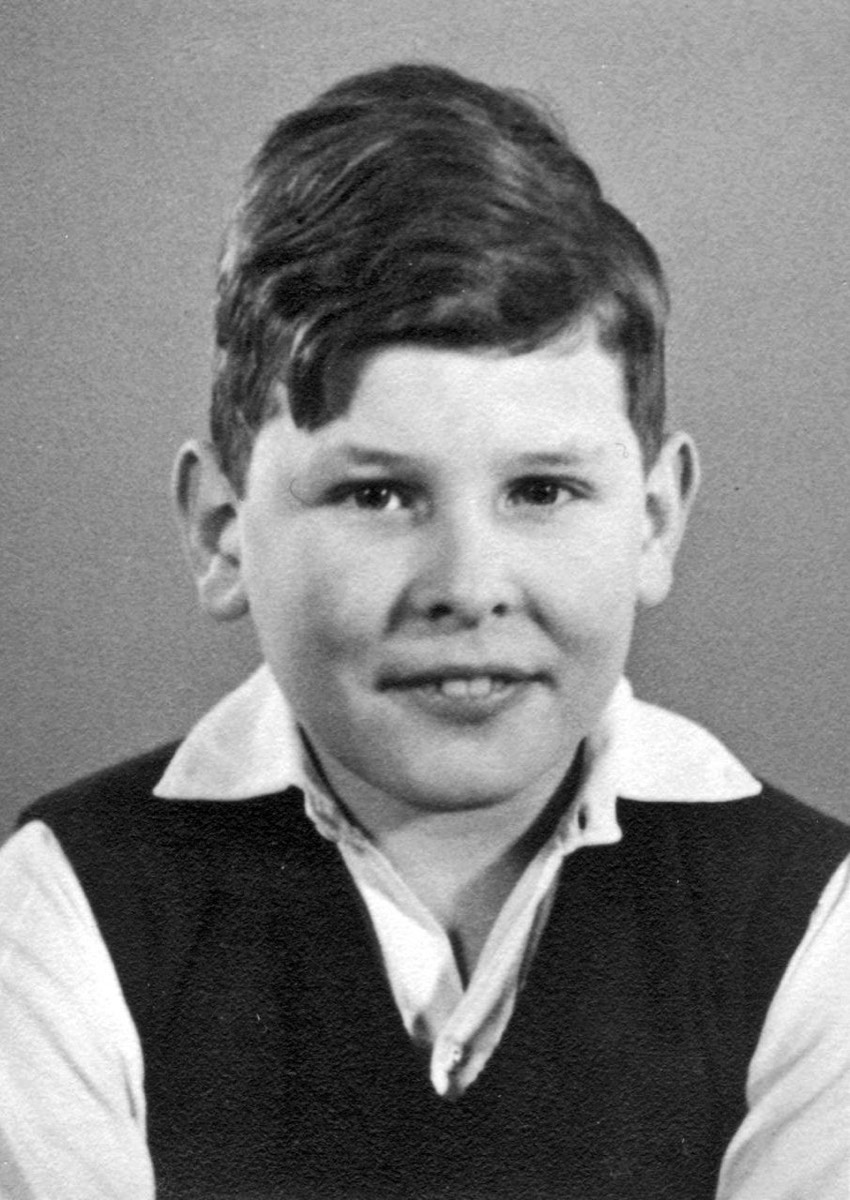

Stefan in his sailor suit.

Stefan Brienitzer, May 1939.

Stefan’s Story

In 1928 Stefan was born in Breslau, a German city of comparative size to Edinburgh. His father was the manager of an insurance company in the city. Despite being from a Jewish family, Stefan said his childhood wasn’t difficult at all and, while he was aware that ‘...things were going on...’, he didn’t pay much attention to them. Let Stefan take up his story:

Early Days

“I knew things were going about but I didn’t, obviously, take them that seriously being only ten years old. I was also blessed with being a beautiful baby and later on quite a handsome ten-year-old boy with blond curly hair which made me un-Jewish in looks. As a result, I could go places where Jewish-looking people wouldn’t be allowed, for example, to picture houses. A circus came once, and I shouldn’t have been there, but I was. I frequently visited places with ‘Juden Verboten’ written outside. I once saw Shirley Temple in a German picture house: unbelievable!

My family was a very liberal Jewish family. Not traditional. We weren’t Kosher. We held the odd festive occasion but not very seriously. I don’t remember ever being in a synagogue, but I do remember being in a church because in the early days we still had a maid. She went home for Christmas and I remember going with her to midnight mass somewhere in Breslau. It was beautiful: I have this feeling of the music and so on and after I came here I wanted to go to a midnight mass in Portobello with friends of the people who took me in and I was most disappointed because the Canon couldn’t sing a note!"

Stefan and his father and mother.

My Family Disperses

"My parents began to worry seriously about what was happening in Germany long before Kristallnacht and they decided to send my sister Hanne out. She was taken to Palestine by Jugend Aliyah in 1938 or ‘39. This organisation took young Jews who would be useful in the creation of the state of Israel. They didn’t want old people. I remember the Customs official came to our house to check that my sister didn’t take things out of the country in her case. In fact, like my father he was an old soldier and he wasn’t in the least interested in what was being packed. He simply sat in the kitchen drinking schnapps and going over old times with my father while I and my mother rushed around gathering all sorts of family heirlooms to get them out of Germany and to give my sister something to help her survive financially. Years later I learnt that everything had been stolen when she arrived in Haifa. As an indication of the thoroughness of the changing times, my birth certificate was altered on 11th January 1939 when ‘Israel’ was added to my name. I and countless others were being marked out as Jews. My older half-brother had gone to the Sorbonne to study in 1933. He wasn’t a Zionist, but he did want to get out of Germany as his views weren’t compatible with the new regime. My other half-brother was a Zionist and he went to Palestine in 1935."

Kristallnacht

"I had seen many SA parades moving along Kaiser Wilhelm Strasse in the weeks before Kristallnacht, but Kristallnacht meant nothing to me at the time. I do remember a Jewish man who lived on the wealthier street side of our flats who tried to get away to Poland but was caught. I remember others being taken and sent, like him, to camps. I saw the Mogen Dovds on Jewish shops which had been destroyed. However, I don’t know why my father escaped that day, but he did. Perhaps friends in the Freemasons helped him, I don’t know. I had an accident at the time when I was travelling standing next to the driver in a tram going along Kaiser Wilhelm Strasse and the controls blew up in a flash. I jumped out of the tram which was moving at full speed and broke my leg. I remember being carried to the Jewish hospital to have my leg treated but they didn’t have much time for me. They were busy treating men from the camps, coming in with frostbite and other injuries. To speed things along they didn’t give me a general anaesthetic but a local instead and I hit the ceiling with the pain when they re-set the bones. I do remember being called names by pupils from other schools while I went to Redigerplatz Schule, a Jewish school."

From the left - Stefan’s half brother, Ernst Cohn, his mother, cousin,

grandmother and uncle. Both uncle and cousin emigrated to the USA.

Kindertransport And Exile

"When 1939 came I was to be sent out of Germany. I don’t remember being told by my parents that I was to leave but I do recall saying goodbye at Breslau station. I was allowed to bring a suitcase with what I needed, and my mother had packed lots of sweets. I ate those for comfort. We left in daylight and travelled to Berlin where we were to spend the night in a hostel, all iron bunk beds. The next day we re-grouped and were joined by a large group of children from Berlin before we caught another train to the Hook of Holland. Many, many years later I discovered that my cousin, Walter, who lived in Berlin, had been on that very train, but I didn’t know it at the time. German border guards came aboard to check what we were taking out and also the validity of any adult’s papers. When we arrived, we went aboard a ferry and came across the North Sea to Harwich. I didn’t know where I was going apart from knowing that I was eventually going to London to be met by an ‘aunt’. She may have been a real aunt, I never knew. I tasted white bread for the very first time on this ferry.

This lady ran up and down the train with my name on a little card and after she’d found me, she took me by taxi to King’s Cross to board the Flying Scotsman to Edinburgh. Now I was really on my own. I went to the toilet at one point and to wash my hands properly, I took off my watch and put it on the windowsill. I’d just been given this watch by my parents. I returned to my seat and quickly realised what I’d done but by the time I got back to the toilet it had gone. I couldn’t tell anyone about it as I didn’t know any English."

Arrival In Edinburgh: July 5th, 1939

"I was met by Mr McGregor and two lady doctors, the Doctors Turk who were cousins of the lady who’d helped me in London. My ‘aunt’ in London had arranged it all through Mr Tom McGregor’s doctor who was Jewish. I caught another taxi (I remember the taxis because they were the first I’d ever been in) to Mr McGregor’s house in Portobello where I was able to phone my parents to let them know that I’d arrived and then I was promptly sick. I was able to keep in touch with them, a few letters, till the war broke out and then via a small number of Red Cross letters.

Eventually I met a few Jewish children my age, but I was very alone at first. To help me keep up my religion, which I didn’t have, I was sent to a synagogue and there I met an old man called Levi who took me to his flat in Clerk Street where he had a widowed daughter and her slightly eccentric piano-playing son, Maurice Cowan."

My Parents’ Fate

"I only learnt about my parents’ fate after the war. They were killed in Auschwitz and my grandmother was taken to Theresienstadt and then to Treblinka where she too was killed. My mother was aboard the last batch of Jews to be taken from Breslau and she and others, realising what was happening, wrote short, last messages on scraps of paper which they handed to a ten-year-old girl who was helping to load suitcases onto the train. This girl was half Jewish, half Aryan and she survived the war to later emigrate to Palestine. By chance she came to live only a few miles from where my sister was living. Later on, my Israeli half-brother’s daughter was doing a PhD and went to Yad Vashem to do research on the Jews of Breslau. When she was looking through some papers, she came across my mother’s note and recognised her handwriting. An unbelievable coincidence. My sister was able to trace the lady afterwards."

Evacuation

"I didn’t get any schooling in Edinburgh at first because, as far as I was aware, all the schools were closed, and I was evacuated to Buckie with Tom’s daughter. I couldn’t speak English but when I came back, I had picked up a few words and spoke in a broad ‘Buckian’ accent. We only lasted three weeks as the girl was homesick. I was homesick too, hellish homesick. We then had teachers coming to the house since there weren’t enough pupils back yet to open the schools. Since Mr McGregor was very generous with the odd nip and cup of tea, everything was very well done.

I consider myself very lucky, something I have often thought about. I survived thanks to my parent’s awareness, their foresight in preparing for the worst, their sacrifice in selflessly saving their children and to being given a home by the McGregors. The McGregors were non-church going Presbyterians who knew what was happening and wanted to rescue a Jewish child. I was that lucky child.”

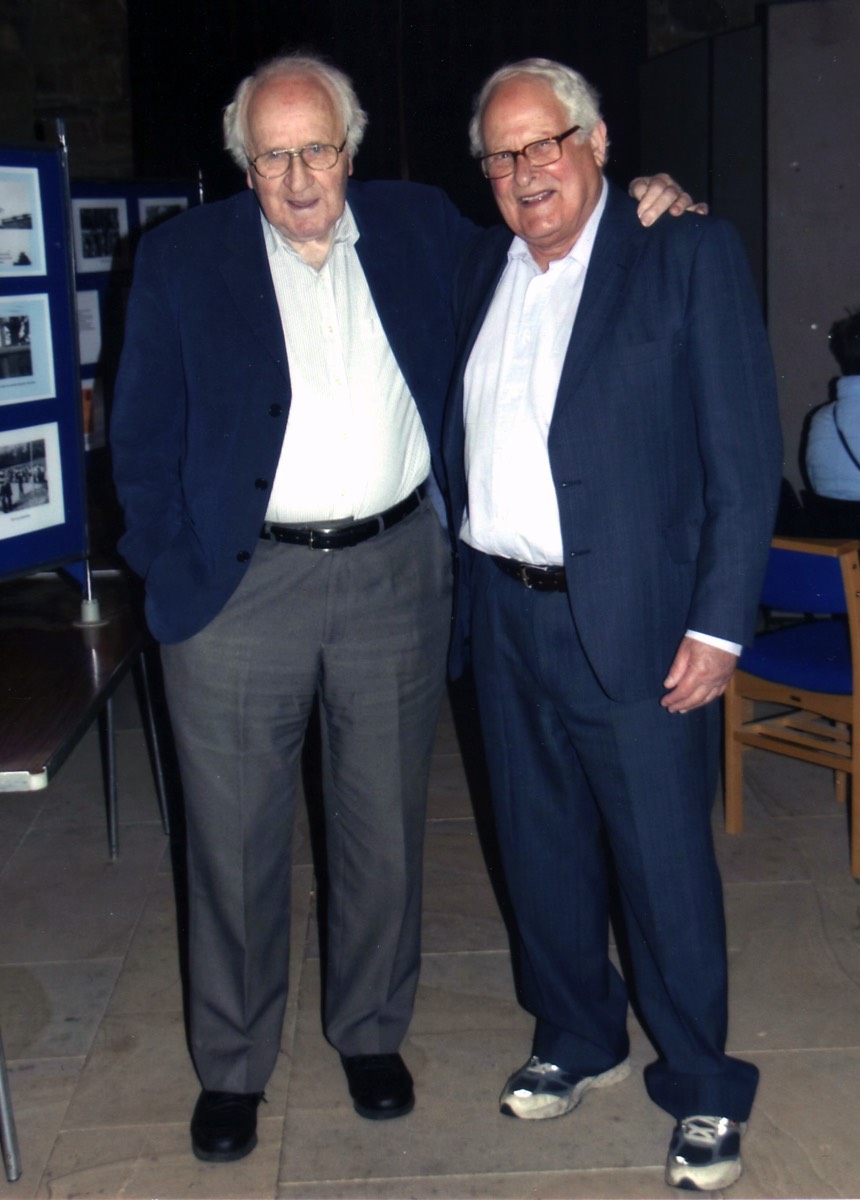

Jack Tully Jackson and Stefan.